September 8, 1945

September 8, 1945

Near Fritzlar, Germany

No. 50 (continued)

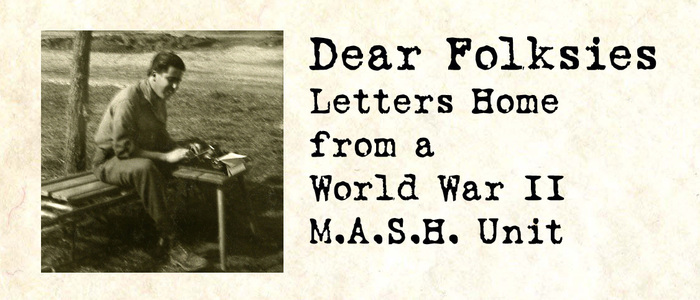

Dear Folksies,

Yvette was taken in a convoy with 1,500 other people to the camp at Auschwitz in April 1944. Of that 1,500, less than ten are now alive. They rode in open flat-cars and part of the time in trucks. When they arrived there, there was immediately a “selection,” and those “selected” were taken off to be never heard of again. The more sturdy were put to work doing various kinds of things.

I believe that it was Ravensbruck about which Yvette was talking when she told me about the evasions she used to get out of work. She had been taken to Ravensbruck in the winter, in open flat cars again and also walking for several days. When they walked, the SSers had orders that if any lagged behind, they were just to shoot them and keep on going. Whenever some poor unfortunate did lag behind, tired out, the German populace, that was always following the prisoners and jeering and spitting on them, would cheer and cheer as the SSers would put the unfortunate person out of her misery. Little wonder that Yvette feels that all Germans should be exterminated and that she would love to do it herself.

Some months after Yvette had been taken, unknown to her, her sister-in-law Jacqueline Bernard was taken prisoner and deported to Auschwitz. When Yvette saw another convoy brought into Ravensbruck one day she asked one lady where the group had come from and how they had fared. The lady spoke of one poor girl whom she did not think was going to live, a girl by the name of Bernard. Yvette managed, somehow, to get to see her sister-in-law and after that she nursed her back to health. From then on they were inseparable, and Jacqueline probably rightfully claims that if it had not been for Yvette she would have died long ago. They had managed to stay together when moved to a camp near Dresden from Ravensbruck, and, when Yvette got an opportunity to leave and head back for Paris, she wouldn’t leave unless Jacqueline could go with her. Permission was granted, and they did arrive in Paris side-by-side.

At Ravensbruck they had to work in a deep pit, building stairs supposedly. About 100 women were working in the pit and about 50 above on the surface. Those on the bottom soon built themselves comfortable places where they could rest, and thus accomplished no work at all — for the Germans were unable to see into the pit, unless they stood directly above it, and whenever they happened to do this the girls were working strenuously. The girls on the surface would always give some sort of a warning well in advance of the approach of the Germans, and the gals would start working seemingly feverishly. Of course, they would all take turns sleeping and acting as the warning group. When, after some weeks, the Germans went down to see what had been accomplished they couldn’t understand why so little had been done.

After Yvette was removed from that job, she was put in a textile factory; but there, because of her hand, she was unable to do the finer work of sewing. So, she was put at the end of the production line to inspect the goods and to pick out the goods that were defective in one way or another. When she started to work, there was a small pile of defective material on one side of her and a large pile of good goods on her other side. However, when they finally pulled her off that job, they did so because they could not understand why the defective pile had suddenly reached the ceiling and the good pile was only about a foot high. Yvette told them that she didn’t know why the stuff got there in such bad condition, nor did she know who worked on those particular defective things, but, see, they all are ruined in one way or another. She, of course, had managed to tear or mutilate the goods as they came to her, thus doing a nice piece of sabotage.

They attempted to get her to work in a munitions works, but she told them that she absolutely refused – that they could and should send her to the crematorium, for they’d never get any work out of her. Why they never acceded to her wishes (to be killed), she knows not.

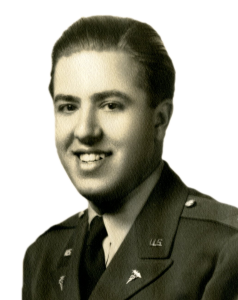

Loads of love,

.

Yvette (center) and her sister-in-law, Jacqueline Bernard (far right) are shown above in this photo taken on the day Yvette and Jean-Guy Bernard were wed in the fall of 1943. In a fortuitious coincidence, Yvette and Jacqueline were reunited in Ravensbruck Concentration Camp in spring 1945.

The March

Who will be able to, or who could understand?

Is there something to understand?

All of this, is it totally incomprehensible?

Or rather totally impossible to understand at all!

The eighteenth of January 1945 – I believe or I know…or perhaps I …

We found ourselves in a kind of corridor, naked.

A kind of metro corridor, in rows of five.

Terribly numerous, advancing by groups, quite slowly

And then, suddenly, after about two hours,

We were made to leave, always naked,

Thrown in a kind of clothes closet.

Each one took what she could.

I had the chance to recover two shoes

And especially a warm, lined jacket.

We were then put on a road, in rows of five

Cold, wind, snow from all sides.

On both sides of the road also, crushed skulls.

The laggards, a bullet in the head.

Red on the white of the snow, horror,

The snow was red with blood of cracked brains…

We must move forward, we must support ourselves.

We are walking.

In a village, some French prisoners, in French uniforms…

Some local residents pour buckets of water on us

They shout, “Down with the whores.” Again, the horror,

The horror of not being able to say anything.

Our horrible horde is nothing, nothing, nothing!

On the third day, a kind of farm.

We could sleep here, on top of each other.

In the morning, a miracle: a hot bowl!

We are walking again.

There is a station and open cars.

It is minus twenty, minus twenty-five or minus thirty degrees.*

The deportees occupy half of a car.

The other half has the SS, the dogs, around a brazier.

Getting on the train, I discover my dress is soaked.

I take it off. I want to wring it out.

Frozen, it breaks in two.

The solidarity brings me a skirt and a knit pullover.

They are great.

We sat on the ice.

We will not die.

The ice, the cold, the wind,

Without having eaten anything except the snow.

For eight days, without bronchitis, without a cold.

We did not die. Why? How?

* In Fahrenheit that would have been -4, or -13 or -22 degrees.