September 6, 1945

September 6, 1945

Near Fritzlar, Germany

No. 50

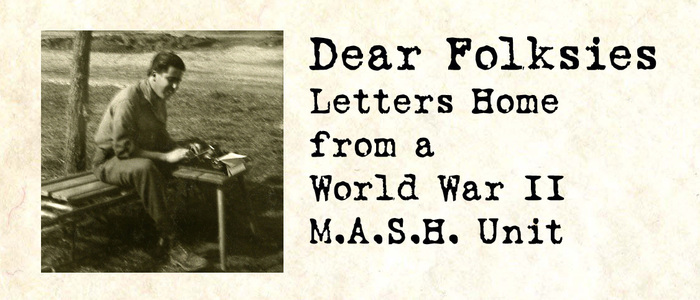

Dear Folksies,

Tonight, I’m going to attempt to jot down a few of the things told to me by Yvette and I am not going to try to make this chronological at all.

Let me preface my remarks about Yvette by saying that she is truly one of France’s great women, and, too, one of its unhappiest. I see in tonight’s “Stars & Stripes” that some French Woman Captain was given some fancy Resistance Award when she recently made a trip to the U.S. Her feat had been to kill some 50 Nazis during some operation involving the blowing up of a bridge during the Occupation. That woman was a Captain! There are only three Women Majors in the French Army, and that is the highest rank that can be given a woman. So that you will see where Yvette really stands, let me tell you that she turned down that rank — the rank of Major!

Yes, when she returned to Paris she was summoned to the Ministry of War and told that they wanted to make her a Major in the Army because of the great work she had done prior to her capture. Yvette, however, had had enough of uniforms, had seen too many SS and Wehrmacht women in uniforms, and didn’t want to have to dress up in any uniform whether it be a Major’s or any other. The Ministry was most insistent, but Yvette was even more so; but finally told them that they could make her a Captain in the Reserves, if they wanted to, but she didn’t want to be active at present. So that is what she is – i.e. holds the rank of Captain in the Reserves of the French Army.

Yvette, prior to the war, was trained in social service work, having obtained what I believe is comparable to a Master’s Degree in that specialty. When the war first came along, she went with the rest of the family to Lyon, but very soon became active in the underground movements for the Resistance. She returned to Paris in the end of ‘42 and became increasingly active, and was soon near the top in the whole movement. While doing this work, she met Jean-Guy Bernard and, in October ‘43, was married in a little town outside of Paris, with only a few Maquis friends as witnesses. As soon as they were married they had to leave the place, and all the friends had to scatter in different directions.

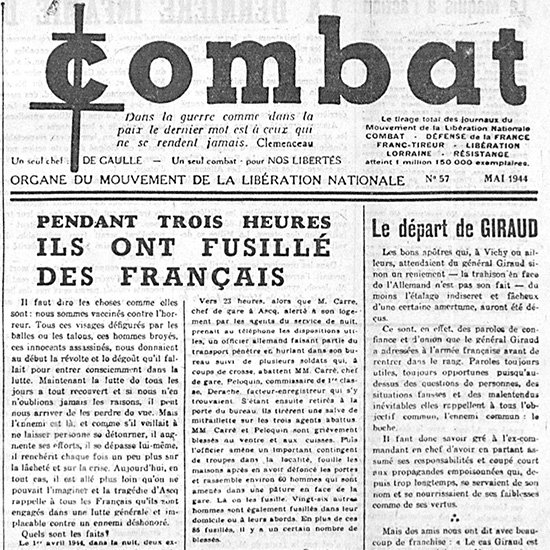

Jean Guy’s father was Colonel Bernard, a well-known French Army man who had, I believe, some Indo-China experience. Jean Guy himself, was a graduate engineer and was also an airplane pilot. His sister, Jacqueline, was, throughout, one of the assistant editors of the newspaper “Combat,” the Paris underground paper — one of the three in the whole of France that continued to publish regularly. It is now one of the most widely read French papers, and Jacqueline is once again on its staff.

Jean Guy and Yvette had to continually change their address, moving at least every ten days so as to avoid detection. If any of their friends were taken by the Gestapo, then they moved immediately for fear that their address or names might be divulged by these friends when under torture. At that, only two people ever knew their address at any one time.

The type of work they did was varied. They collected all sorts of information concerning the movement and strength of the German troops; they directed sabotage against the German Army; had trains blown up; and relayed all information they obtained by short-wave to England or later to Algiers.

There are now certain streets in Paris down which Yvette cannot walk. Why? Because, when she returned to Paris she attempted to thank the numerous people who had, unknowingly, been working for her during the Resistance. They knew her at that time either as “Claude” or one of the other numerous names that she had used, or they may not even have known any name of their superiors, nevertheless, they did the work assigned to them at all times. These men of whom I speak, in particular, were the doormen at apartments and hotels, grocery-men and little shop-keepers who, for the most part just passed on information, written or verbal, to the proper channels — the channels that led to Yvette or Jean Guy. Yes, Yvette went around and thanked these people, but now if she goes down these same streets she is mobbed — they throw their arms about her, try to give her things, etc., etc.

Loads of love,

.

Jacqueline, as René tells his parents, had been a journalist with “Combat,” the underground newspaper of the French Resistance. Jacqueline, who had joined the Resistance in 1941 in Lyon, was deported to Ravensbruck Concentration Camp in Germany in July 1944. After her return to Paris, she again became a member of the editorial staff of “Combat,” which had become a daily newspaper with Albert Camus as editor.