September 27, 1945

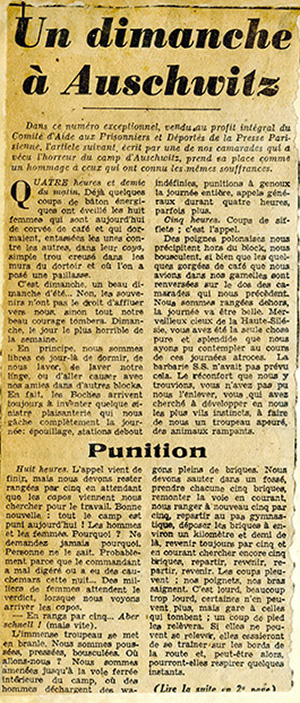

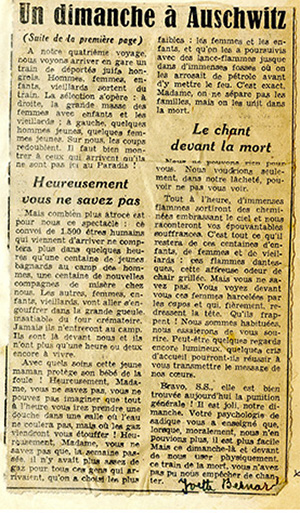

The following is a translation of an article written by Yvette Baumann Bernard, René’s second cousin. A clipping of the original article, which was published in a French newspaper sometime in the second half of 1945 (perhaps on September 27) is reproduced in the sidebar.

The following is a translation of an article written by Yvette Baumann Bernard, René’s second cousin. A clipping of the original article, which was published in a French newspaper sometime in the second half of 1945 (perhaps on September 27) is reproduced in the sidebar.

The preface reads in part, “The following article, written by one of our comrades who experienced the horror of the Auschwitz camp, takes its place as an homage to those who experienced the same suffering.”

A Sunday in Auschwitz

By Yvette Bernard

Four-thirty in the morning. Already some energetic blows from the stick had woken the eight women who are today on coffee duty and who slept, heaped one against the other, in their coya, a simple hole dug in the walls of the dormitory, and where a bench had been placed.

It is Sunday, a beautiful summer Sunday…no, memories don’t have the right to come flooding to us, lest all our beautiful courage will fall.

In principle, we are free on this day to sleep, to wash ourselves, to wash our laundry, or go chat with our friends in other blocks. In reality, the Boches always manage to invent some sinister pleasantry that completely spoils our day: delousing, standing in place indefinitely, punishments on the knees the entire day, general roundups lasting four hours, sometimes more.

Five o’clock. Whistle blasts; it’s roll call.

The Polish poignes rush us from the block, jostling us so much that the few gulps of coffee that we had in our bowls are spilled onto the backs of our comrades in front of us. We are lined up outside, the day is going to be beautiful. Marvelous heavens of the Haute-Silésie, you were the only thing pure and splendid that we were able to contemplate over the course of these atrocious days. The barbaric S.S. could not prevent that. The comfort that we found in it, you could not take that away, you who looked to develop in us the most vile instincts, to turn us into a frightened herd of crawling animals.

Punishment

Eight o’clock. Roll call just finished, but we must stay lined up in rows of five while waiting for the capos to come get us for work. Good news: the whole camp is punished today! The men and the women. Why? Never ask why. Nobody knows. Probably because the commandant had bad digestion or had nightmares during the night… Thousands of women wait for the verdict, when we see the capos arrive.

–In rows of five… Aber schnell! Quickly! The enormous herd put itself into motion. We are pushed, hurried, jostled. Where are we going? We are brought up to the interior track of the camp, where some men are unloading wagons full of bricks. We must jump into a ditch, each taking five bricks, back up the track, arrange ourselves again five by five, go off with gymnastic steps to deposit the bricks to a spot one and a half kilometers away, return each time in groups of five, running to get five more bricks, going, coming, going, coming. The blows rain down; our wrists, our arms bleed. It’s heavy, much too heavy, some can’t do it any more, but attention to those who fall; a kick gets them back up. If they can’t get up, they will try to crawl along edges of the road and, maybe then, they might catch their breath for a few minutes.

On our fourth trip, we see a train of deported Hungarian Jews arrive at the station. Men, women, children, old people leave the train. The selection is in progress: to the right, the large mass of women with children and the old people; to the left some young men, some young women. On us, the blows double. It must be shown to those who are arriving that they’re not here in Paradise!

Happily You Don’t Know

But how much more excruciating is this spectacle for us: the convoy of 1,500 human beings who just arrived will become no more than, in just few hours, a hundred young inmates in the men’s camp, a hundred new companions in misery among us. The others, women, children, old people, will become engulfed in the huge, insatiable mouth of the crematory oven. They will never enter the camp. They are there before us and they don’t have more than an hour or two left to live.

With what care this young mother protects her baby from the crowd. Happily, Madame, you don’t know, you can’t imagine that soon you will be taking a shower in a room where water does not run, but where the gas will suffocate you! Happily, Madame, you don’t know that, last week, there was not enough gas for all the people who arrived, that the most feeble were chosen: the women and the children, and that they were pursued with flamethrowers up to the immense pit where they were hosed with kerosene before being set on fire. That’s right, Madame. They don’t separate families, but they unite them in death.

The Song Before Death

We can do nothing for you. We wish only, in our cowardice, that we could not see you.

Later, huge flames will come out of the glowing chimneys kissing the sky, and will tell us of your dreadful suffering. That is all that remains of the hundreds of children and women and old people; these Dantesque flames, this horrible odor of grilled flesh. But you don’t know. You see in front of you these women harassed by the capos, and who proudly straighten up. They strike! We are used to it, we will try to smile at you. Maybe some looks still bright, some welcome calls will succeed to send you the messages from our hearts.

Bravo, S.S., the general punishment has been discovered today! It is pretty, our Sunday. Your sadistic psychology has taught you that when morally we cannot take it any more, it is easier to use us physically. But this Sunday, in front of the train of death, you could not stop us from singing.

—————————